Denise Leto

"MASK, PAUSE, MASK":

SOMATICS AND THE LANGUAGE OF GRIEF AND DISABILITY IN THE WORK OF VIOLET JUNO AND NORMA COLE1

The somatic manifestation of grief is much written about, and according to many books on the subject, from it we are supposed to create new meaning. But grief is a rhythmic, oneiric state of being. It is a repetition and modulation of not-knowing. Thought, language, and bodily sensations loop. When grieving, all the senses are heightened and dulled at the same time. It hurts and if there is physical or emotional pain a priori to a specific loss then it can feel to me, at least, like the quotidian reality of incessant descent. By descent I mean the fathomless nature with which disorientation can prevail. This is because death, of late, has been a constant in my life; this past year was one of multiple losses–six significant family members passed away. They died from various causes within complex, persistent medical, social, and political conditions: rheumatoid arthritis, heart attack, diabetes, Alzheimerís, cancer, the co-morbidity of bipolar disorder with years of alcoholism and drug abuse, and the intersection of multiple health issues with domestic violence. In particular, I lost my mother, sister and my dearest friend and greatest mentor in a matter of months. At this juncture the idealization of embodiment is impossible.

In my experience, death is not clinically artless nor is it an operatic expiry, and there persists a stark want of metaphor. The dying process is a visceral telescopic–not an imagining into imagined events or bodies but a witnessing and sharing in the direct experience of blood, breath, elimination. It is not a constellatory phantasm of post-experience, post-beauty, post-ability but the unpretentious candor of the present moment ending–whatever is the opposite of time. Whether it is sudden, prolonged, violent, catastrophic, or expected it tells the story of the body: that specific body. How it moved in the world, how it functioned, how it was seen, the perspectival shifts of expectations and identities. Was it ill, was it a body in difference, was it disabled, was it "abled," was it resourced? At risk? Privileged? Impoverished? Marginalized? As long as a body exists in what is inscribed as a normative mode, thereby earning presence and meaning, we enter the story as if death were a kind of fairytale and grief its predicted redemption. If a body exists in a way that subverts normative modalities, and thus re-defining presence and meaning, then we sometimes exit the story as if death were monstrous and grief its expiation.

Within my own body dwells subtle and not so subtle difference: I have dystonia, a neurological movement condition and disability which affects the production of "fluent" speech, involves chronic pain, and, though very nearly invisible in my body, there resides a torrent of spasmodic muscles which impact daily life. However, in recent months, the narrative of my previous embodied experience has now been re-written by complicated bereavement. I have all of the classic reactions to grief: loss of appetite, sleep disruption, encumbered concentration but also a wearying in the way my brain communicates with my body. I can feel it: a kind of profound fatigue as information. I simply canít converse with my body, with my mind, with others the way I did before. The dystonia courses through me with no effortful, conscious attempt at the fiction of internal mediation. I stare at my body in bewilderment, completely disconnected from its processes while at the same time more rigidly bound by them than ever. I look at others with measured distraction as they try to communicate with me. I am listening: but as a ghost might.

Embodied grief can beget internal and external isolation: the bereaved may disappear into their grief as the world may disappear into its disavowal of grief. This is not always the case, of course, but complicated bereavement involves an immersion and an excruciating pain both emotional and physical that is not easily extant in a social or professional milieu. For me, muscles contract; vocal chords seize amid my daily physical struggle. However, it is the grief that feels merciless. Not my unheroic body, which, though coiled in a new veracity within which it is transformed in space and time, is nonetheless here and therefore here.

Because disability is part of that story, it can sometimes be cast as the depreciative, encompassing antecedent. In this context, death becomes an occlusive and existentially feared failure and grief its misfortunate scourge and aftermath. If the survivor or the deceased lives or lived with disability, the conversation may be given over to platitudinal complication and alienating wonder. How did/does she do it? I fall here, too. I ask these questions, too: of others and myself. We grasp. We falter. We err. Grief is often rendered tragic regardless of the individual circumstances surrounding the life and the death. And this presupposes the notion that the disability or the embodied difference was and is a universally grieved condition. Furthermore, the medicalization and institutionalization of death, its placement outside the realm of daily discourse and experience, is directly equivalent to the exile and depersonalization of grief. Disability is seen as a kind of micro-death of ability and death as a macro-release of disability. The flip-side of problematizing embodied suffering is to romanticize it. Conversely, romanticizing disembodiment problematizes it.

I have found that pathologizing grief in an already pathologized body can also make contaminate the cultural rituals of consolation. We often donít know what to do for the mourner. We donít know what to say. But we hardly knew before. Since the form of dystonia I have is not easily visible and primarily audible, it can sometimes be benignly or inadvertently misinterpreted until it appears in a way that is impossible to miss. Activities such as conversing in a public place, ordering a coffee, or talking on the phone become fraught with mis-steps, disruption, decelerated rhythm and most of all an exhausting, stealth effort at voice-passing. The unpredictable and episodic nature of its manifestation in my body and speech makes for a confusing, constant form of adjustment and adaptation in verbal exchange. Add the vagaries of grief to the interpersonal mixture and it is even easier to get lost in the language of loss. The grief compounds all relational interaction. In the pall of mourning, whatever your own body is made of becomes even more itself.

In this essay, I wish to explore the multifaceted experience of grief, language, and disability by considering the work of the transdisciplinary performance artist, visual artist, and writer Violet Juno and the poet, artist, and translator Norma Cole. In thinking about ideas of somatics, grief, and disability, I have gravitated toward artists who work in different media and who embody language spatially and with a dimensionality not evident in written textual forms alone. For both Juno and Cole, their work embodies art on and off the page as they address or move toward questions of loss, textuality, and physicality. There is no equivalency between grief and disability. There is just the experience of grieving in a disabled body or a body in a state of difference, in pain, or in trauma and what that might feel like or look like in the irresolution of words, story, lineation, graphic scores, sound, music, props, movement, installation, painting, and photography.

To engage with ideas of grief and loss is to take on the body as it is–and take it out of eased construction, out of processural reach. In her work, the transdisciplinary artist Violet Juno enters into these questions, literally, with her own body. Her pieces are a kinetic sculpture: multi-sensory and immersive. She uses a vocalized and textual story-cycle structure. The performances are composed of a series of prose poems or short stories and vignettes rather than a traditional, chronological narrative. She contends with loss and the sometimes "undiagnosable," perennially misdiagnosed, or cruelly dismissed and therefore unnamed character of disability–visible and invisible. If a condition or state of being remains unnamed then it is outside the discourse of medical, therapeutic–alternative or traditional–treatment or intervention. Information gathering itself becomes a colossal task. How can you gather information about something that has yet to be identified but nonetheless is something that you are suffering from and whose very suffering troubles and impedes the often fatiguing and arduous acts of research: sitting at the desk, working at the computer, getting to the library, finding a good doctor, picking up and putting down the phone, navigating health insurance, managing the medical bureaucracy?

Junoís performance piece entitled, "Edgeworthy" explores ideas of embodied suffering and the lived reality of disability within a background of precariously exposed urban and natural places. 2 In it she makes known what it is like to live with a condition–fibromyalgia– whose symptomology is refuted and even mocked. As a disability that is profoundly misconstrued, doubted, and may be largely invisible to others, it becomes real to the world only when Juno externalizes the complexity of the experience and the severity of the pain. She expresses it with the language and somatics of performance, and raises it from the subterranean miasma of invalidation to the uncompromising exposť of what she knows to be true.

The setting for "Edgeworthy" evokes extreme environments: abandoned industrial zones, the detritus of a deserted desert, and the cold mechanics of doctors offices and hospital rooms. It is a perilous internal and external landscape in which Juno employs live performance, voiceover, projected images, and a recorded soundscape throughout the show. The stage is encircled with various props: an oxygen tank or propane tank, barbed wire, a hospital cart, an IV tube, a roll of rusty bedsprings, an old shoe, tin foil, and pieces of rusty, twisted metal. It is an apocalyptic, deconstructed proscenium. The spatial relationships are tight, almost piercing. Time feels sticky and enervated. Things move slowly in the piece: her gestures, her body, her speech, the soundscape, and the visual imagery.3 The lighting is a shade of reddish pink that imbues a horizonless, pillowy feel or, depending on the text or movement, a nausea of tilting threat. All of the props and set elements were scavenged from an abandoned shipyard that had become an urban dumping ground and even though this detail is not overt, it can be felt in the way the objects are placed and in Junoís movements. The effect is the stage as body, as flesh with a menagerie of sharp and sometimes eerie set-objects and props encompassing her actual body. It suggests a desolate, vacant landscape yet one enlivened with motion and ritualized in presence and words.

Juno in Edgeworthy - Image 1 (Photo credit M. Juno)

At different points in the show Juno wears a clear silk, plastic layer, which appears to be three aspects of a covering: a hospital gown, a raincoat and a doctorís coat. As the show opens she is swathed in white cloth bandages. Her face, feet and hands are exposed. Rather than looking as if she is bandaged on the outside though, her own body is both the bandage and the wound. She wraps and unwraps the bandages. Dresses and undresses them. The stage and her body are the dual-seats of physical and emotional pain. During the production, there are variations of choreographed movement and non-movement: she stands for an instant with her back to the audience, sometimes at a 3/4 turn. She kneels, sits cross-legged, moves her arms in graceful circles, falls, lays down curling and uncurling her legs, and walks haltingly, bent at a precipitously forward angle leaning on canes of rusted metal. This is not a metaphor for the disabled body or a hyperconscious nod to issues of mobility. Crucially, it is Juno walking in a way that she sometimes has to walk. Itís just that in this context that particular movement is performative. In daily life it is daily life. She engages a lived and perceived contortion and makes visible the invisible, the supposed "ugly" and the unmitigated ugliness and brutality of the medical establishment.

In parts, she remains still in soliloquy speaking in real-time or interconnects with the props while her recorded voice plays. Juno uses the voiceover as an adaptive strategy. Her disability does not allow for the continuous vocalized output of stamina and energy needed for the full length of "Edgeworthy." Language shapes the enactment and trajectory of the performance. Its mechanization fills what otherwise would have been necessary silence. Juno uses it as a conduit of somatic inquiry and a stark interrogation of the environment. In her script and stage notes for the beginning of the performance, she writes:

Movement

Pause

Movement

Backwards

Slo-mo

Pause

Unwrap

bandages

from torso

mask

pause

mask

Take off

gloves/pants

Go to canes

Running in

place with

canes (2)

While enacting these noted movements, she recites:

I am sitting in the doctorís office. She is looking at the papers in front of herÖand then she leans toward me conspiratorially she says, there are a lot of doctors in the medical community who do not have ÖkindÖ things to say about people like you with your condition. She stays in her bent forward position looking at me waiting for my response. I realize my body had leaned towards her slightly mirroring her posture expectant that she was going to tell me a secret, something valuable. I look at her and I think, how very third grade. I slowly lean back, hook my arm over the back of the chair, and spread my knees. How very cowboy. I know, I tell herÖ.Iíve had this for 20 years. Just imagine how many doctors Iíve met before you. I think back two decades. All I ever wanted to be when I grew up was surprised…(2)

Juno is alone in her act of discovery regarding her body, its sensations, pain, transformation, and knowability. There is no healer by her side listening, exploring, and bearing witness much less lending accurate expertise, open-minded curiosity or refined empathic attunement. Instead she encounters blunt disregard, erasure and isolation–negation as loss and therefore a compounded grief. To my mind, she is, in part, looking for the surprise of being seen: to have communion at the edge of things, to be able to withstand this place alone and together.Junoís project is not to set-up an equation in which the mystery of her body will be solved or heroized by certainty, by an exchange of perfect language, but to question the daily vagaries of what her body is or is not communicating to self and other. In the following excerpt, taken from the fifth prose poem about a quarter of the way through the piece, Juno evokes the unredeemed ground of the hospital and disturbs the rush of treatment, the fear, the call for help, the tactical coalescence of otherís near her:

In my sleep Iím running and I can hear the footsteps of all the other runners in the hospital. There is a cacophony of sound, all the feet hitting the ground punching the tile. We are all running in place in our rooms. We are running together, collectively moving the hospital forward. We are all running, lying in our beds, running in our heads. We are racers, greyhounds, that have gone down lying on our sides waiting for the painkiller. (2)

When inserted into the medical narrative, Juno must always be prepared with a rebuttal and the articulation of the body as justification. She is tasked with questioning existing information and seeking new information; most importantly she re-defines and discerns a body of information that can serve her body.

In the following vignette, Juno pushes a hospital cart in circles. With metal tongs she begins to throw white feathers on the stage –which at first look like bandages–little by little then all of them at once. She cups her hands over her mouth. She then opens and closes them. She sits down and begins to jam the feathers in her hair with jerking, forceful motion while speaking the following:

He said, what I have found is that it takes a while to get a doctor to trust you. It takes a while before they understand you are not emotional about it. You just want to know the truth and you deserve to know the truth…even if itís extrapolated or only partly substantiated or just plain not pretty. But they donít tell you. It takes years sometimes for them to relax and realize youíre not going to cry or break down or beg for something they canít give you or do something stupid just out of fear or desperation. What they know–itís just facts and opinions, pieces of information. …Itís your problem what you do with it. A doctorís office is no place for emotion. Itís a business; itís about information exchange. You give them information. They give you information. (5)

Juno in Edgeworthy - IMage 2(Photo credit M. Juno)

For Juno, "information" isnít just discrete pieces of mechanized revelation, quantitative evidence, or ameliorative science. She is not asking for the absolution of a flawless diagnostician. In her world, in her art, information is beyond passive reception of the noted or the power of wrong-headed, static, institutionalized, established "truths;" it is animate and evolving; it is active participation in the pain and its expression. It is knowledge of the experience and the sharing of it: a breathing, porous, textual, human relationship that will impel inward, backward, forward, and circuitous motion. Information is a conversation of language and community.

She asks for the same multidimensionality from us that her body is giving you the audience, you the doctor, you the naysayer, or you the loved one. Here, she explains:

Why say anything at all without the words I, wracked, is, mundane, with. Vacate the narrative. Why say anything at all because, after all, wonít, slithery, falling, pump. Leave it behind, any attachment to the sound and heft of words. If you must, pare back the coat, the skin, strip as to leave not even the definition or shape, not even the bones or structure, just marrow, a scent of direction, a hint of curve. Resist any urge to rebuild the context, create a horizon line, the angle of light. What good would that do? Donít tell about the crack in your vision or the seam in my face. (5)

But of course she does tell and with a brilliantly capacious and nuanced artistry of language and movement. Juno renders the manifestation of grief in her body and her sense of loss both intra-personal and interpersonal. Her body is the story and the anti-story. The lie of triumphalism fades as she creates an imaginary of the unseen and the unspoken, the telling and the untelling.

Juno in Edgeworthy - IMage 3(Photo credit M. Juno)

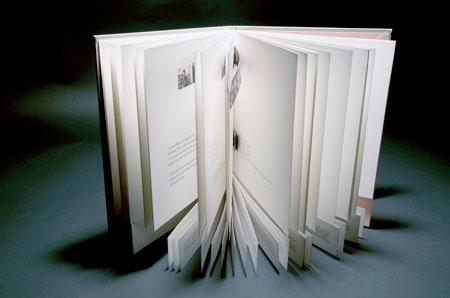

In 2004, the work of the poet, artist, and translator Norma Cole was featured in a retrospective exhibit, Poetry and its Arts: Bay Area Interactions 1954–2004 hosted at the California Historical Society in conjunction with the Poetry Center at San Francisco State University. This work involved a site-specific gallery installation and subsequently a fine press book of text and graphic images entitled Collective Memory. The installation, designed by Cole, took the form of three different writerís rooms: " Living room circa 1950s," an Archives Tableau–a nod toward the American Poetry Archives–and a room entitled "House of Hope," a suspended sculpture. Over the four months that the exhibit ran, Cole, performing as "poet" in the installation, wrote the poems that would become the fine press book, which was published by Granary Books in 2006. According to their website:4

The text comprises several sections: "Prelude" is followed by "Speech Production: Themes and Variations" which is illustrated throughout with full-color photographs by Cole…. This section is followed by "Collective Memory: History" which is illustrated with Coleís line drawings…. Another section, "House of Hope –in Memoriam, Montien Boonma 1953-2000" is separately bound into the covers at the bottom of the book in such a way that it runs parallel to the above noted text. "House of Hope" is composed of 416 quotations–"notebook phrases" [from Coleís own notebooks]–from a wide range of artists, poets, filmmakers, philosophers, and other writers. (np)

Collective Memory

In the exhibit, poetry is multidimensional; it is not insular or isolated. Cole is present–she is the poetís body at work, an active part of the installation. This is significant both as the transformation of public space into a place of collaborative embodiment and as a private offering into her creative process. She is the maker of her own body and art while also responding to outside tactile forces, sounds, words and influences in real-time. Cole exists in a moment of live art/performance writing, subject/object interplay in a room that is an artifice in a room. The installation suggests the physicality of walking into a book, into the layers and facets of language. The way our bodies sit, move, write, paint, draw, observe, interact, and communicate.

In 2002, Cole suffered a stroke, which affected her speech and mobility. In her essay, "Why I am Not a Translator," she writes:

A test case in neurobiology: when I had my stroke four years ago, two areas of language were affected. One was a motor problem. Speech production was knocked out in the brain. Therefore I couldnít talk at all. And Iíve had to refigure, little by little, how to make speech occur with mouth, teeth, tongue…and then for many people who have strokes, the brain swells, doesnít settle for a while…so we have aphasia and canít think of words: the words for up and down; the simply conventional words; and the words that stand for ideas. I am here to tell you that one has ideas even before one has the words to say them. Ideas, or images. No tabula rasa. (258)

I am here to tell you.

For Cole, speech may be the conveyor of–but not the precursor to– ideas. Verbal ability or difference does not equate to facility with spoken or printed language. The mechanics of speaking and the neurology of language production are linked in a way that foregrounds the ontological dilemma of expression. In the poetry of Collective Memory, the brain drives non-normative language production just as it does "normative" processes. Traumatic brain injury can upend accepted notions of conventional communication and culture creation. Neuro-diversity in speech and language production shapes whatís on and off the page. In Colesí work, whatever form the self takes is the self.

I am here to tell you.

Coleís book of poetry, Natural Light, published in 2009, is divided into three parts: "Plutoís Disgrace," "In Our Own Backyard," and the aforementioned "Collective Memory." The poems engage with ideas of philosophy, politics, and various forms of violence to the body and to the mind. "Collective Memory," which is the last section, begins:

Speech production: themes and variations

exhibit

exhibition

ribbons

vandals

the ribbons of vandals, the vandals

of ribbon, scissors of ribbon,

ribbons of scandal

sculpture of

ribbons or

strips

strippers

strip clubs

exhibitions: temporary inhibitions, my semblables: collective guilt:

donít leave your filthy shirt, your own fifty-yard line. What would

be the motive in that "kind of temporary performance"? (Christo

& Jean-Claude) (43, 44)

The poetic line is sometimes one word and, by drawing all the attention to it, more is at stake just as the re-acquisition of spoken and written language is at stake: phoneme by phoneme. This is not an aphasic dreamscape. The transposing of words in that condition–pre-poem–is not intentional, it isnít word play; it is word work. In the poem, associations grasp, they alliterate, they reverse paratactically and they may or may not assemble denotative or contextual indicators. The language to give communicative form to ideas takes on a new form. There is the "aphasic" line on the printed page and the silenced resonance, the mouthing of the words in the brain that blank and trouble expression. There is loss in the interstices of language: looking for nouns, verbs, adjectives, for the signifier that matches or approximates the signified: "…my semblables…." (44). How the words and ideas in the poetry collection pre-existed in the exhibit is the archive of the past voice searched by the same mind.

The short stanzas throughout the poem are sometimes interspersed with longer lines and quotations and they may at first glance give a kind of listing ease–like a grammar primer. But there is no pedagogical agenda. No cipher. No key to a linguistics question. No amplitude of the sentence. The result is that Cole renders a poetics of re-imagining what it is to speak and write. Words disturb words. Images disrupt images. Repetition remakes repetition. Serializing the many choices of words to say…? Cole suggests that as Christosí physical work The Gates is vandalized, so is its temporality. Likewise, the cut of words in "Collective Memory" is predicated upon what time has made of them.

While reading "Collective Memory," it is possible to see evocations of neurological tests and procedures for measuring aphasia that examine, among other things: expressive and receptive processes, spontaneous speech, speech comprehension, the repetition of words, phrases, and sentences. The tests might ask you to repeat simple phrases or associate words together or words with objects. These tests inevitably raise questions about the politics of subjectivity, cultural context, the language(s) of disability and interaction with the medical industry, hospitals, specialists, speech pathologists, the apparatus and processes of possible recovery and so on. Cole writes:

quote

quotation

quit

quoting

quit it

unscripted

quoted scripted

quote script?

script quote

Why would I like the word moving like a cripple among the leaves and why

would I like to repeat the words without meaning? (45, 46)

The cadence and consonance in these lines occur concurrently but oscillate at different time scales. Embodied language converges the moment thought is scripted as marks on a page to be read. The scripted performance of oneís own words, the translative quoting of otherís words, and the physicality of handwriting constrain and imbalance. Questions of verbal exchange, the restricted mobility of speech and body, the tangle of rhyme, of chance, of formal device latch and linger–the movement and execution of a word as interference in its own sequence. Physical or emotional suffering and loss of language-making shapes the "I" of Norma Coleís work differently, which in turn forces the "I" of the reader to think differently.

In Collective Memory– the installation–Cole uses quotes as part of a three-dimensional perception of writerly space. She offers a way to look at the words of others as part of a larger scaffolding that is her own work. In the book, she uses them to formulate a sense of language as art-body, sometimes in extremis, sometimes in wit: the text as hers, yours, mine. She uses quotations from Wallace Stevens, Dante, T. S. Eliot, Robert Duncan, and Charles Olson among others. For example, in the following stanza she quotes Stevens in the penultimate line and then mentions the source poem in the last line:

for all intents and purposes I has slippage: forthwith, the body can

never recede "Exchequering from piebald fiscs unkeyed: ("The

Comedian as the Letter C…")." (62)

The line, "exchequering from piebald fiscs unkeyed" is a collection of "c" sounds embedded in the larger sound compendium that is "Collective Memory." Taken from canto V, stanza three of "The Comedian as the Letter C," it also suggests a humor and a topsy-turvy musicality. These sounds in this context accent Coleís words that came before the body was at risk and the words that came before the quote: "I has slippage: forthwith, the body can never recede…."

She also alludes to Whitman:

sweet flag: calamus

very cloudy: books flying up to the sun

you, little cloud of more

than human form, setting fire in back of the

brain. (56)

"Calamus" is Whitmanesque and it is also a wetland reed that is sometimes used to treat strokes. Here, Cole employs a printed language that suggests traveling vertically away from human capacity aground. And who is the "you" in back of the brain? There is doubling, tripling, layering, humor and scale in the poem. Consider:

to be at music

beyond waterlily lake

at the level

of local language

this means ours

geophysical

pelagic

Petulant pixies had completely rearranged the living room. Stand

here more or less. Lessness. We can put it like this: petulant lover

identified with her. Or over-identified with her. (50)

The first line refers to Coleís book of essays, To Be at Music. Herself in herself. There is immediacy and expanse–the level of local language and the physical movements of the earth, as in oceans. There are synaptic pixies confounding the water, the beloved, the line, the body and its greater and lesser movements in spatial relation.

In the following stanza, Cole gives a glimpse into the gauge and gradation of altered experience. It is elegiac and exclamatory. Excited. Oxygenated. There is a reference to "Muskrat Ramble," a jazz composition that is part of the standard repertoire and emerges here as a connective and collective allusion juxtaposed with the tedium of a hospital room. While recovering? While writing? Is it a memory in the threshold of motion and sound? The loss of the illusion of assurance in the nominal, in the familiar, in the tactile nature of language when it is transformed, in the body, in movement:

Frosted Flakes, the biggest box you ever saw! Letís ramble,

muskrats! The rooftop oxygen gets right into my room!

"Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

cannot bear very much reality." (T.S. Eliot, "Burnt Norton") (52)

Coleís is a poetics of magnitude and specificity, indirection and ex-direction. It is a verbal space in upheaval taking place on and off the page. The interaction and continual process of her visual art with her literary art makes non-verbal and verbal forms of language exist in a flux of one. I am here to tell you.

In considering the power of Norma Coleís and Violet Junoís work, I understand more that both what one self-defines as disability and self-experiences as grief can be co- radical states of being. It takes space and time. My specific body, in grief, in disability has a greater need for space and time. The language that I use to translate this experience is suspect. Words are no longer so easily conductive. Each death vanquished what I used to know. The body staggers formative ideas, tapers entropy. It responds in the moment to sounds before meaning. Part of what confounds is that life and the dying process are dynamic, but death is static. In an instant there is movement and non-movement, breath and non-breath. Whatever is the opposite of sentience. Grief, loss, death, and the body in transformation are not about proximity and distance, since that has become nonnegotiable; it has to do with the private and the communal. Conversing with, or not, those still here. Or not.

Notes:

1. This essay is dedicated to Martha, Virginia, Josephine, Matthew, Byrna, and Ann.

2. Written, staged, and performed by Violet Juno and directed by Chelsea McKinnon, "Edgeworthy"

was first performed in 2003 at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, California and in 2004 at The Arches

Theatre and the Center for Contemporary Art in Glasgow, Scotland. "Mask, Pause, Mask" is from the script

and stage notes. More about her work can be found at her website: http://www.violetjuno.com

3.The sound art duo Opaque created the soundscape for "Edgeworthy."

4. http://www.granarybooks.com

Works Cited

Cole, Norma. Collective Memory. Multimedia Art Installation. Poetry and its Arts: Bay Area

Interactions

1954–2004. San Francisco: California Historical Society, 2004.

-- Collective Memory. Emily McVarish. New York, NY: Granary Books, 2006.

-- Natural Light. New York, NY: Libellum, 2009.

-- To Be At Music: Essays & Talks. Richmond, CA: Omnidawn, 2010.

-- "Why I am not a Translator Ė Take 2." Beauty is a Verb: The New Poetry

of Disability. Eds.

Jennifer Bartlett, Sheila Black, and Michael Northen. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos

Press, 2011.

Juno, Violet. Edgeworthy. Writer and performer. 2003. Video.

--"Script and Stage Notes." Edgeworthy. Personal correspondence.

15 Jan. 2014. Email.